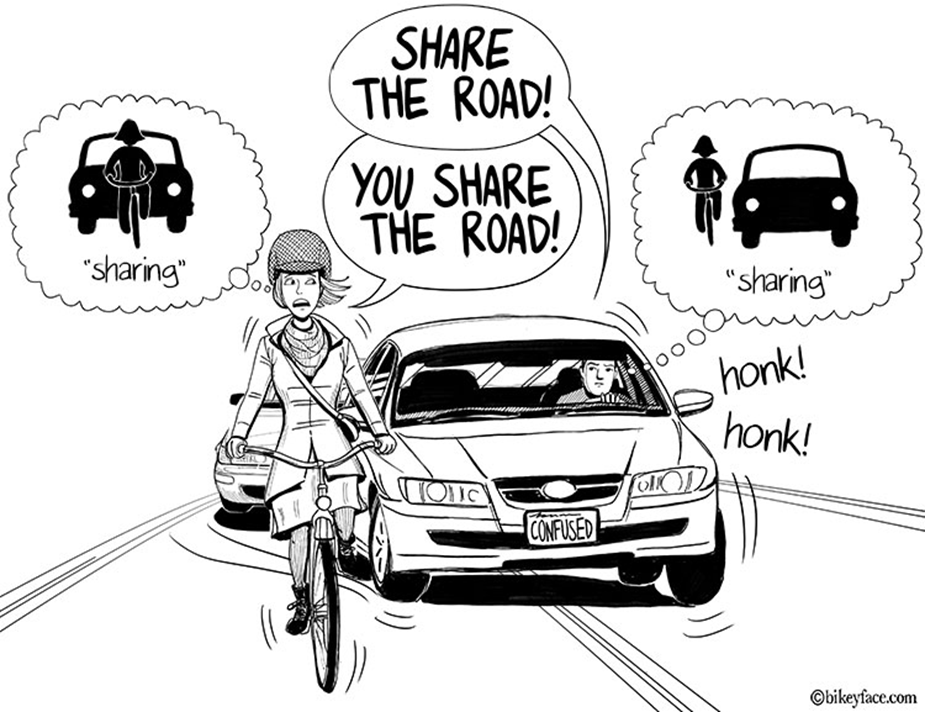

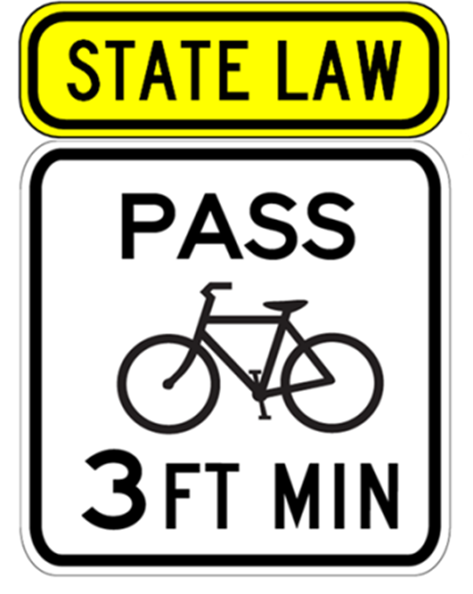

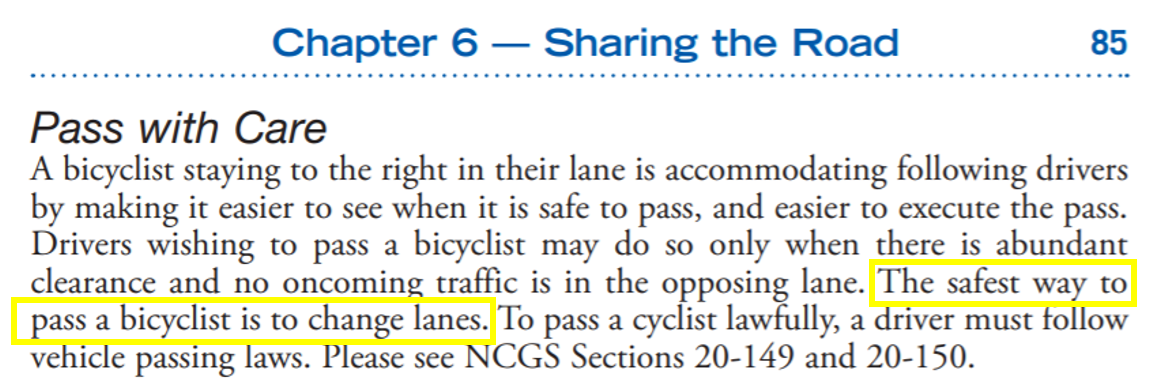

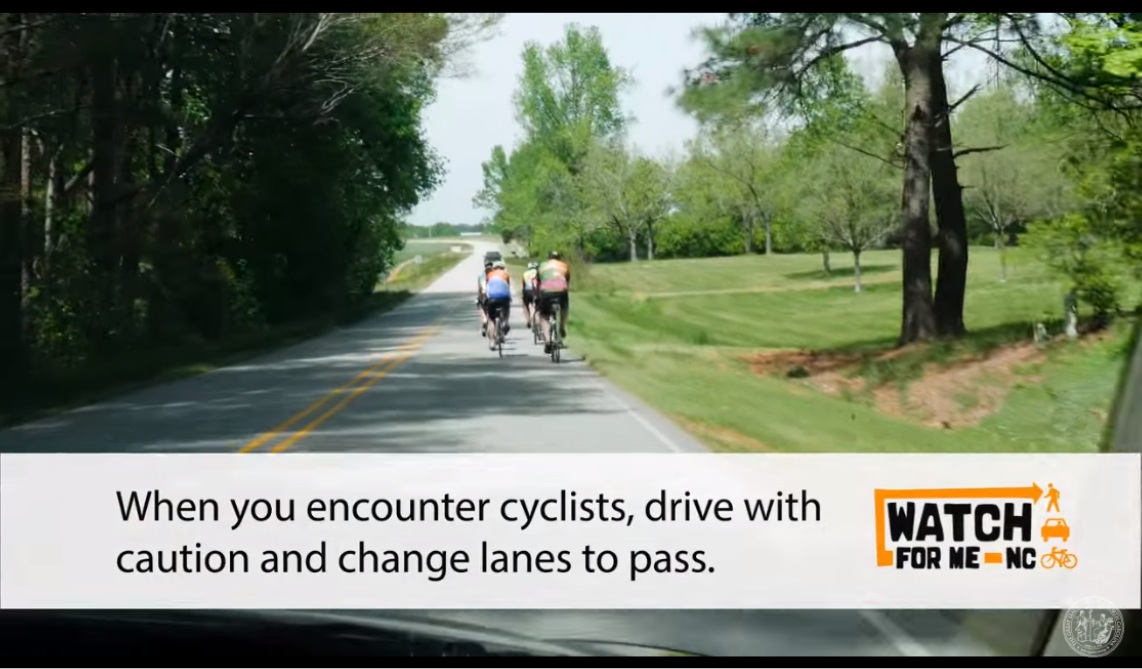

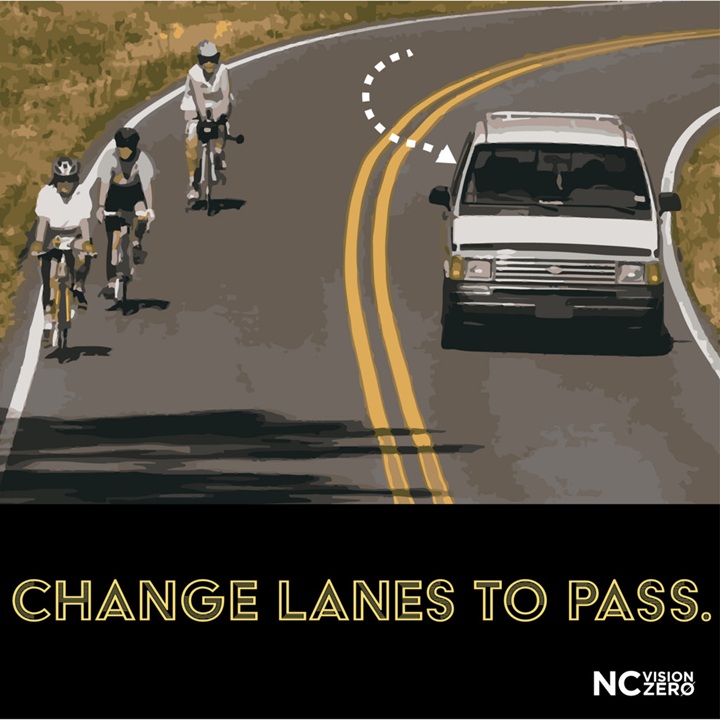

The Working Group brought together by NCDOT pursuant to House Bill 232 to study bicycle safety laws held their final meeting November 18th. After approving last meeting’s minutes, the group focused on the legislative directive to look at whether cyclists should be required to ride single file or allowed to ride two or more abreast. The committee unanimously approved a motion to recommend no new regulations on riding abreast (there was consensus that two abreast is often safer than single file), and instead for NCDOT to develop an education and outreach program (with funding) to promote safe group riding practices, safe cycling, and safe motoring, including advice spelled out in the resolution drafted by NCDOT that the preferred method of passing bicyclists is a lane-change pass.

Here are some points made during the discussion.

- UNC HSRC (James Gallagher) and enforcement representative Chris Knox both scoured general statutes and reached out to experts and did not find anything that prohibits riding two or more abreast

- Absent law against, cyclists riding two or more abreast is legal. Steve Goodridge (BWNC) pointed out that a few municipalities in NC have traffic laws that may conflict with state law as they require riding single file

- James Gallagher also searched research and found none that suggested riding single file is safer.

- Each person on the committee was asked to share their view for the record on riding two abreast. No one thought it was safer or provided rationale to support requiring single file. Virtually all shared thoughts that supported riding two abreast such as:

-

- No recorded hits from behind when riding two abreast. Single file riders have been hit from behind.

- Riding two abreast makes the bicyclists more visible, appear “bigger”

- Riding two abreast makes motorist pass in other lane, which is safer (most crashes are from same lane passing)

- Riding two abreast tightens group and thus facilitates passing for motorist

- James said based on above points, riding two abreast is “probably” safer and added that only 3 states restrict it (39 states specifically allow it)

The committee had previously taken action on some of the other legislative directives – here is a summary of actions taken from previous meetings. These included recommended legislation

- Allowing crossing of double-yellow line to pass bicyclists when safe

- Requiring rear lighting or reflective clothing

Thank you to our cycling supporters that attended the meeting; some came in from Charlotte.

NCDOT will now assemble the committee recommendations into a report document, and write its official legislative recommendations into that document. The draft report and recommendations will be made available for public comment and likely revisions before being provided to the legislature. BikeWalk NC and the cycling community will need to pay close attention to the report document, but even more important is what the legislature decides to do with it.