By Steven Goodridge

NCDOT and the state legislature are facing an inescapable reality: not only are fossil fuel tax revenues not keeping up with the costs of building and maintaining a road system that suits the speed and convenience preferences of motorists, but the state is also failing to protect public safety adequately on those state-maintained roads.

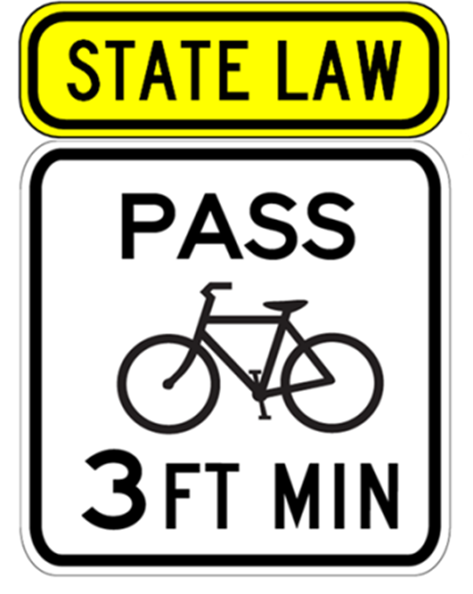

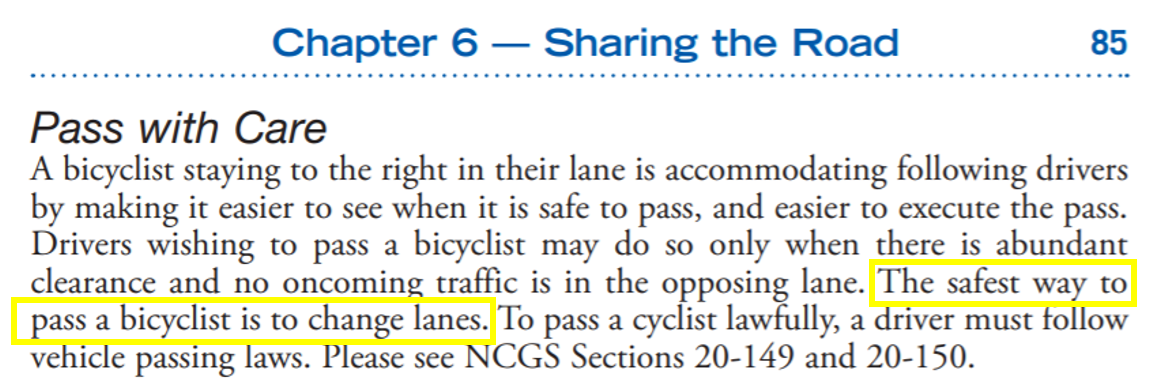

The cause of the public safety problem on state-maintained roads is not the slow speed and vulnerability of bicyclists. Our humanity is a virtue for which we need never apologize. The cause of the safety problem is the high speeds at which motorists are attempting to travel on ordinary roads shared with other people. In 2013 when NCDOT adopted its goals of implementing its “comprehensive statewide plan for improving bicycling and walking conditions across North Carolina”, it focused on five main principles – mobility, safety, health, the economy and the environment. But that same year, the NC General Assembly defunded that plan and has since directed NCDOT to spend billions of tax dollars on limited use roadway and turnpike projects, while defunding bicycle and pedestrian projects.

If motorists are endangering other members of the public, then it is reasonable to expect motorists to pay to mitigate that danger through road improvements and other means where possible. Similarly, if motorists wish to enjoy a higher level of convenience on shared roads, then it is reasonable to expect motorists to pay more. Yet it is clear that fossil fuel revenues will still not be enough, especially as people change their travel modes and switch to alternative energy sources and higher-efficiency vehicles. Other revenue sources will be needed to build and maintain those most important through roads that link our homes, schools, parks, and businesses. All members of the public have a stake in the success of this, not just motorists. For thousands of years, roads were funded by general taxes such as property taxes; it is only recently with the increased public costs created by motoring that states began to rely so heavily on motoring use taxes for revenue. The false narrative that state roads are intended only for motoring may be a side effect of this over-dependence on motoring revenues (although NCDOT’s own failure to build such roads to community-friendly multimodal standards contributes to this as well). It is long past time to stop viewing our state roads as motorways and to again view them as ways for all members of the public, paid for by all members of the public.

In a nation founded on personal liberty, an individual’s basic freedoms are not proportionate to the amount that the government chooses to tax them. Taxes are a means to obtain revenue to pay for public facilities and services, and a fair tax system is proportionate to one’s impacts and ability to pay. We know from experience that annual bicycle registration revenue schemes are highly regressive even when the fee is barely high enough to cover administrative costs, resulting in very low compliance rates and public relations problems for police when interacting with low-income and racial minority bicyclists. A more sensible approach to increasing revenue would focus on where the money is, and be designed to operate with minimal overhead. Bicyclists are already spending millions of dollars in state and local taxes on their bicycling equipment, activities, and food, but the state chooses to spend these revenues as part of the general fund rather than on roads and infrastructure. Let’s have a substantive discussion about increasing revenue for public safety improvements, instead of proposing programs that will only cause pain for people who travel without a car.

In the meantime, BikeWalk NC asks that the North Carolina General Assembly end the prohibition on using state funding and allow for the design, development and construction of Stand-Alone Bicycle and Pedestrian Projects to facilitate safe active transportation. BikeWalk NC also urges the General Assembly to consider codification of North Carolina’s Complete Streets Policy which would integrate the costs of maintaining and developing cycling and walking infrastructure.