Consensus building around a better paradigm for bicycling safety

by Steven Goodridge

A driver pulling a wide trailer nearly sideswipes a bicyclist in Petaluma, California

The Problem

Unsafe close passing, especially at high speeds, is one of the most common safety concerns expressed by bicyclists who use our state’s roadways. Beyond just frightening bicyclists, unsafe close passing contributes to a large share of car-overtaking-bicycle collisions. Although darkness, impaired driving and distracted driving are factors in many overtaking-type collisions, a growing body of evidence including video recordings and personal injury investigations shows that attempted same-lane passing of bicyclists may be the most common overtaking-collision failure mode, particularly in daylight.

Same-lane passing of bicyclists is a flawed concept of operations. Most marked travel lanes are too narrow to allow a motor vehicle to pass a bicyclist within in the same lane at safe distance. On rural roads, travel lanes are typically about ten feet wide. A Ford F-150-based pickup or SUV will almost certainly strike a bicyclist if attempting to pass entirely within a ten-foot lane, as shown below.

Wider, twelve-foot lanes found on some newer roads provide more maneuvering space for large trucks and buses, but don’t allow such vehicles to pass bicyclists within the same lane.

Safe Passing

The space occupied by a bicyclist fluctuates as the bicyclist maintains balance. This operating space is at least four feet wide, and preferably five feet wide, according to the AASHTO Guide to the Development of Bicycle Facilities.

Safety advocates recommend a bare minimum of three feet of separation between a bicyclist and an overtaking motor vehicle (more distance is required as speeds increase). For a motorist to pass at least three feet away from the bicyclist’s dynamic operating space, on most roads the driver must move across the left lane line and well into the adjacent lane.

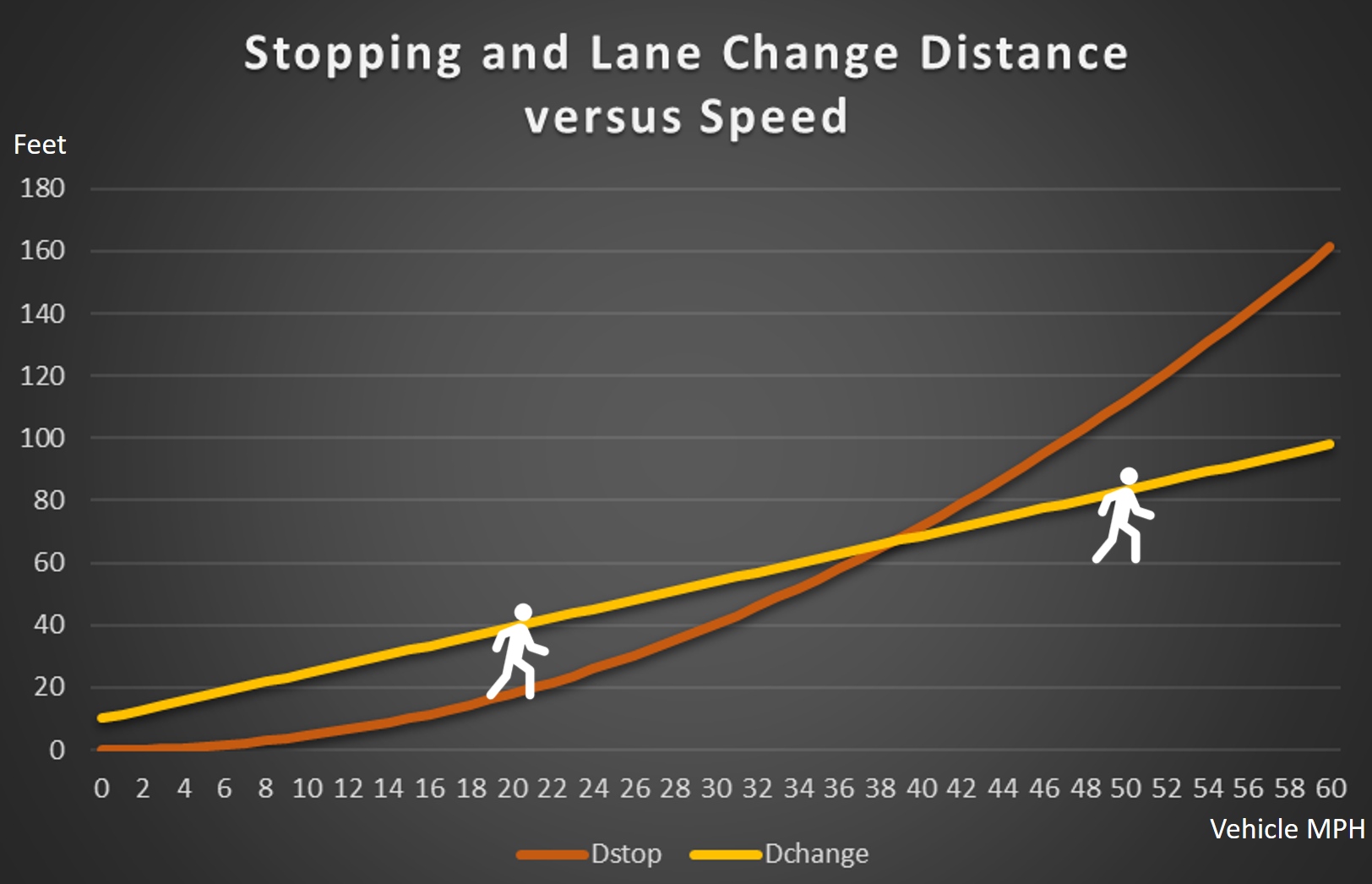

Movement into the adjacent lane requires that a motorist yield to any vehicles already using that lane, which often requires slowing, looking, and waiting until conditions are appropriate. It is important that this thought process begin early, so the motorist has time to decelerate to the bicyclist’s speed if need be. A driver whose concept of operations is a same-lane pass will often approach the bicyclist at high speed until the lack of space becomes apparent at close distance, which is often too late.

Changing motorists’ default concept of operations from “same-lane” to “next-lane” passing is essential to improving bicyclist safety on the roads we have. Whether the motorist must move three feet, five feet, or completely into the next lane for a safe pass, the motorist must be prepared to look and wait for traffic in the next lane to clear, and this mental process needs to start as soon as they see the bicyclist.

Messaging

Public messaging can influence public behavior, but to be effective it must be targeted, clear, and actionable. Past efforts by state and local DOTs to improve motorist-overtaking behavior through slogans and signage have had mixed results.

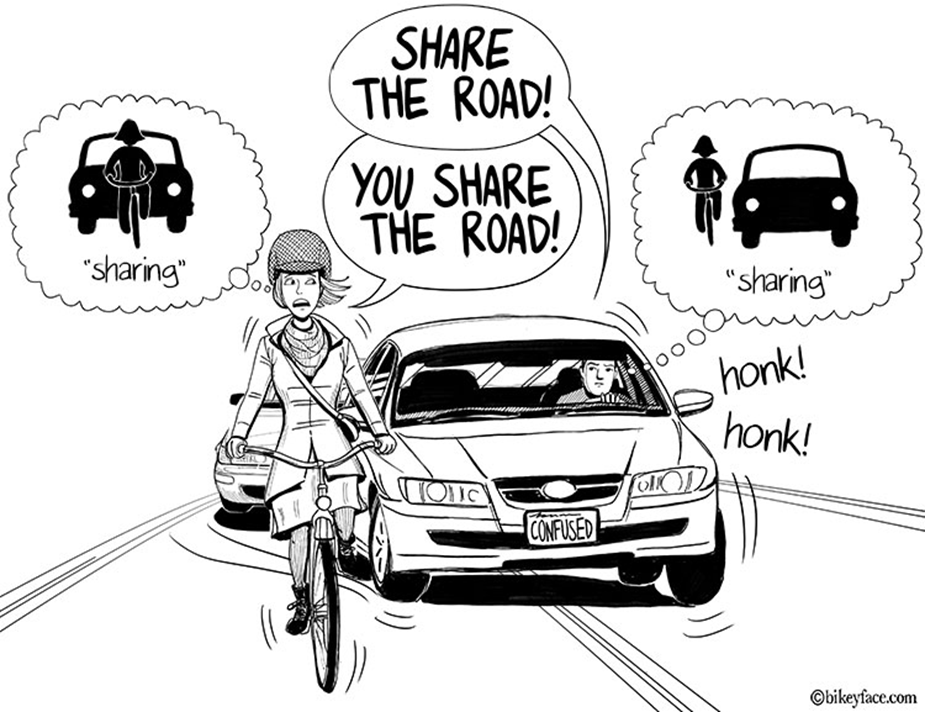

The most visible messaging to date is the “Share the Road” slogan and signage. “Share the Road” has been widely criticized by bicycling safety advocates as poorly targeted, ambiguous, and unactionable. It allows two completely opposite interpretations, same-lane and next-lane passing, as lampooned by cartoonist Bikeyface:

“Three Feet to Pass” and other “N-feet” messaging, signage, and laws seek to quantify a safer distance for passing of bicyclists, contrasted to the minimum two-foot legal requirement for passing closed vehicles. While public understanding of safe distance is important, “N-feet” messaging does not address the flawed concept of same-lane passing that contributes to high-speed overtaking crashes. For instance, California’s 3-feet law provides an exception that allows for closer passing in narrow lanes, and police in California have buzz-passed bicyclists and harassed them for not riding far enough to the right to facilitate a safe same-lane pass despite inadequate lane width to do so.

“Three Feet to Pass” and other “N-feet” messaging, signage, and laws seek to quantify a safer distance for passing of bicyclists, contrasted to the minimum two-foot legal requirement for passing closed vehicles. While public understanding of safe distance is important, “N-feet” messaging does not address the flawed concept of same-lane passing that contributes to high-speed overtaking crashes. For instance, California’s 3-feet law provides an exception that allows for closer passing in narrow lanes, and police in California have buzz-passed bicyclists and harassed them for not riding far enough to the right to facilitate a safe same-lane pass despite inadequate lane width to do so.

Many knowledgeable bicyclists leverage the defensive practice of lane control – riding near the center of the travel lane, and/or riding two abreast – to deter unsafe same-lane passing in narrow lanes. The general effectiveness of this practice has garnered it support by many in the traffic engineering profession and has resulted in new traffic control devices that encourage and support it. The ITE Traffic Control Devices Handbook provides guidance to install shared lane markings, aka “sharrows,” in the center of the usable width of a travel lane when that shared width is too narrow to facilitate safe same-lane passing. Lane-centered sharrow markings can be found on many roads that are popular with bicyclists but feature narrow lanes.

The “Bicycles May Use Full Lane” sign is another common treatment used to convey the legitimacy of lane control by bicyclists on narrow-laned roads. A study of message effectiveness conducted by George Hess and M. Nils Peterson found that both motorists and bicyclists understood the meaning of “Bicycles May Use Full Lane” sign better than shared lane markings and “Share the Road” signage in terms of where bicyclists may operate within marked travel lanes.

The “Bicycles May Use Full Lane” sign has not been without controversy. Some in the traffic engineering profession have objected to use of the sign, for reasoning varying from misunderstandings of the state’s slower-vehicles stay-right law (which treats marked travel lanes and unmarked roadways differently) to concerns that, as a white regulatory sign, it incorrectly implies a legal prohibition against using any part of the bicyclist’s lane when overtaking (motorcyclists are the only users in North Carolina who enjoy statutory protection against any side-by-side use of their lane by another motorist). Advocates with BikeWalk NC are confident that these misunderstandings and concerns will eventually be put to rest. However, the “Bicycles May Use Full Lane” sign and discussion are tangential to the key actionable message that needs to be delivered to the motoring public: how and when to overtake safely.

Change Lanes to Pass

Change Lanes to Pass

A clearer message to describe best practice for passing bicyclists on ordinary roads is “Change Lanes to Pass.” Performing this safely involves three simple steps:

- Slow Down. Don’t run into the bicyclist from behind while preparing to take action.

- Look and Wait until Safe. Other traffic is likely to be using the adjacent lane. Wait until it is clear.

- Change Lanes to Pass. Move across the lane line to ensure there is adequate separation from the bicyclist.

A yellow “CHANGE LANES TO PASS” warning plaque could accompany the standard bicycle warning sign (MUTCD W11-1) for roadside use. Most existing “SHARE THE ROAD” plaques are installed on roads with narrow lanes and could be directly replaced with a “CHANGE LANES TO PASS” plaque; however, sight distance may be a consideration when determining where to locate such signs.

Solid Centerlines

A significant obstacle to public promotion of lane-change passing has been the prevalence of solid centerlines on most of the narrow rural roads used by bicyclists. Many police officers and other public officials have considered these markings to be inviolable, but in practice most motorists do cross solid centerlines to pass in-lane bicyclists when the clear sight distance is sufficient for safety. Engineering policies for marking dashed centerlines assume that the vehicle being passed is moving at near the maximum posted speed limit; this requires a much longer clear sight distance than when passing a slow moving bicyclist. Because many locations that allow safe next-lane passing of bicyclists are marked with solid centerlines, North Carolina recently joined many other states in modifying the passing law to allow passing of bicyclists in such locations when all other legal conditions for safe passing are met.

NC General Statute subsections § 20-150 (a) through (d) define limitations on when passing is permitted based on clear sight distance, oncoming traffic, and other safety factors. Subsection (e) restricts passing in designated no-passing zones. In 2016 subsection (e) was modified to allow passing a bicyclist if all of the other safety conditions are met and the driver provides at least four feet of clearance or completely enters the next lane. This legal change brought the passing law into alignment with the routine behavior of prudent motorists, and opened the way for police and other public officials and motorists to begin a substantive dialog about recommended practices for passing bicyclists on narrow two-lane roads.

Recent Messaging

Since the 2016 change in the passing law, NCDOT has begun incorporating “change lanes” into numerous bicyclist safety messages, including an update to the Driver Handbook and materials produced by the Watch for Me NC and Vision Zero programs.

BikeWalk NC advocates that this progress continue with actions including the following:

- Phase out “SHARE THE ROAD” plaques in favor of “CHANGE LANES TO PASS” plaques

- Educate law enforcement about changes to the passing law and recommended technique for passing bicyclists

- Produce motorist education/PSAs on safe passing practices

- Update driver education curriculum

- Change-lanes-to-pass law

When public understanding and support for safer passing of bicyclists has grown sufficiently, it may become politically possible to pass legislation in North Carolina to require it. A few states including Delaware, Kentucky and Nevada require motorists to change lanes to pass bicyclists under some circumstances, such as when there is more than one lane serving the direction of travel. A change-lanes law makes it easier to identify unlawful passing maneuvers, and any overtaking collision with a bicyclist in the same lane becomes prima facie evidence of a violation by the motorist. However, there is a danger that without sufficient public understanding and support, pushing for new legal restrictions on motoring behavior near bicyclists could result in the attachment of new restrictions on where and how bicyclists may ride – for instance, prohibiting effective defensive practices such as lane control. For this reason, advocates with BikeWalk NC believe that a comprehensive safe passing education campaign should be pursued before further legislation on passing in our state.

Although roadway engineering modifications such as well-designed and maintained bike lanes and wide paved shoulders can often eliminate the need for motorists to change lanes to pass bicyclists, many or even most roads where unsafe close passing occurs are unlikely to see modifications due to the expense. Most are two-lane roads where the state or municipality does not own wide enough right-of-way to add to the pavement width. “Change lanes to pass” is a necessary part of any long-term strategy to support safe and pleasant bicycling on our road system.